Peggy Albright’s book is the first extensive study of Richard Throssel (1882-1933), a Creek Indian adopted into the Crow tribe, where he lived and worked beginning in 1902, photographing the Crow extensively for both artistic and official purposes.

After a brief introduction to Throssel as “an Indian who had no tribe” and the Crow community that took him in, Albright makes an extensive examination of his aesthetic foundation as someone with the ability–as well as the opportunity–to mediate between his adopted culture and the outside world.

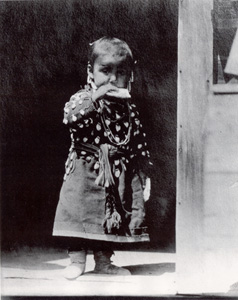

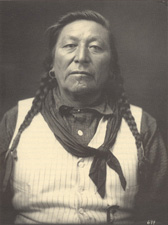

She then reproduces numerous Throssel photographs with explanatory comments by contemporary Crows.

Albright is very self-conscious in presenting Throssel’s work; while the rediscovery of a thousand photographs of Native Americans taken by a Native American comprise a significant historical cache, she is sensitive to the exploitation, inaccurate interpretation, and political controversy such publications have invited in the past. The pictorial style of Native American photography pioneered by Edward Curtis often romanticized (or simply misrepresented) their subjects for dramatic effect, and Albright invites us to consider the extent to which Throssel participated in this tradition.

Albright is very self-conscious in presenting Throssel’s work; while the rediscovery of a thousand photographs of Native Americans taken by a Native American comprise a significant historical cache, she is sensitive to the exploitation, inaccurate interpretation, and political controversy such publications have invited in the past. The pictorial style of Native American photography pioneered by Edward Curtis often romanticized (or simply misrepresented) their subjects for dramatic effect, and Albright invites us to consider the extent to which Throssel participated in this tradition.

Unlike many of the coffee table books, this book presents seventy-four of Throssel’s plates but its emphasis clearly is on the photographer’s relationship with his world; it is a thoughtful, painstaking examination of who Throssel was, who his subjects were, and the extent to which his work actually contributed to documenting and understanding Crow society.

Albright’s discussion of Throssel’s life and work provides crucial context for all his photographs. Another study might have either sanitized or politicized Throssel’s apparently paradoxical biography, but Albright gives us the facts and allows us to draw our own conclusions.

Until this publication, Throssel was known primarily for a series of thirty-nine photos marketed to an affluent White audience under the title “Western Classics,” which self-consciously sentimentalize the Indian past while proclaiming Throssel an “authentic Indian” in their advertising.

Until this publication, Throssel was known primarily for a series of thirty-nine photos marketed to an affluent White audience under the title “Western Classics,” which self-consciously sentimentalize the Indian past while proclaiming Throssel an “authentic Indian” in their advertising.

Throssel took both romanticized and commercial photographs of the Crows at the same time he was doing more authentic work, sometimes even capturing ceremonies prohibited by the federal government. His photos for the Indian Service, depicting day-to-day conditions on the Crow Reservation, ostensibly were directed at improving health conditions but emphasized the need to adopt White ways in order to achieve that goal.

Numerous photos depict transitions between traditional and contemporary elements of Crow life without condemning the loss of the native culture. But to dismiss any part of Throssel’s work because it seems politically incorrect is a mistake. Throssel’s political and artistic energies were rooted in his personal experience.

In these years, Crow land was threatened repeatedly by federal abrogation of treaties and schemes of white business interests. Throssel may or may not have welcomed some degree of enculturation (after all, he was fascinated by a technological art); he seemed to see it as necessary for survival. But Throssel saw himself as an ambassador for both sides, not as a broker or shill for the Whites.

In these years, Crow land was threatened repeatedly by federal abrogation of treaties and schemes of white business interests. Throssel may or may not have welcomed some degree of enculturation (after all, he was fascinated by a technological art); he seemed to see it as necessary for survival. But Throssel saw himself as an ambassador for both sides, not as a broker or shill for the Whites.

When U.S. citizenship was forced upon him as a means of stealing his land allotment through taxation, he responded by campaigning for Native American rights, becoming an elected member of the Montana State Legislature.

Richard Throssel wrote public letters in newspapers and petitioned federal agencies in Washington, D.C., with some success, to protect Native American interests. Albright successfully conveys a sense of a man and a people swimming hard to stay afloat among the tides of history. Few photographic records so poignantly depict people dealing with cultural conflict in their daily lives. The humanity displayed here is powerful.

Source:

This review is copyrighted (c) 1997 by H-Net and the Popular Culture and the American Culture Associations. It may be reproduced electronically for educational or scholarly use. The Associations reserve print rights and permissions. Contact: P.C.Rollins at the following electronic address: Rollins@osuunx.ucc.okstate.edu