Before the invasion of silk, sequins and designer labels, the highest fashion west of the Mississippi was the elk-teeth dress.

There was no mistaking the status of a Crow woman wearing her tribe’s signature gown of blue or indigo trade wool covered by 500 elk canine teeth. They wore their wealth on their sleeves. Because only two teeth from an elk are suitable, each dress represented years of hunting and hard work.

Winona Yellowtail Plenty Hoops wore such a dress on her wedding day. In the nearly 70 years since, she’s stitched thousands of elk teeth to dresses of her own creation. There have been so many dresses, Plenty Hoops has lost track.

Plenty Hoops is one of the last of her tribe who makes her own clothes according to old ways. Her handiwork is known from her home in the Valley of the Chiefs clear up to Arrow Creek, and even beyond.

She was named a master artist in 1994 by the Montana Arts Council. Her work has even been purchased by the Smithsonian Institution.

But Plenty Hoops will be 85 next month, and her abilities to create have been stripped away by diabetes and arthritis.

“I can’t thread my needle any more,” she said one recent afternoon while sitting in a wheelchair at her home south of Lodge Grass. “I can’t sew.”

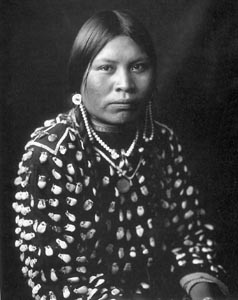

Photo by Richard Throssel  |

Plenty Hoops doesn’t follow patterns or keep written instructions. When she eventually moves to the other side camp, many worry that a pillar of Apsaalooke culture will crumble, her knowledge forever lost.

“There’s very few of us left,” she said.

Elk eat grass and twigs, but they have two teeth in their upper palate made for tearing meat. The upper canines – known as the “ivories” – are evolutionary misfits with no purpose, said Bob Garrott, a Montana State University-Bozeman professor of ecology.

“All mammals evolve to have incisors, canines, premolars and molars,” he said. “As they evolve, their teeth slowly modify to their diets.”

Since the stone age, these bulbs of ivory have caught the attention of hunters. They were different, polished, smooth. Some historians think they were among the earliest forms of jewelry.

Crow tradition once required successful hunters to give away the ivories to members of their hunting party who didn’t down an elk.

When a man killed his first elk, the ivories were saved for a necklace for his bride or for his daughter.

Although usually only for special occasions, most Crow women continue to wear a beaded necklace with the two special elk teeth.

Although elk were a valuable source of meat and clothing, Plenty Hoops doesn’t know exactly why her people placed such a high value on their ivories.

“It started way back before Columbus,” she said. “I don’t know how far because it’s way, way back.”

The white settlers soon noticed the white nuggets of bone prized by the Crow, Cheyenne, Lakota and other tribes across the High Plains.

During the market hunting era, about 100 years ago, there are records of mass slaughters of elk specifically to collect their ivories, Garrott said. Many of the teeth ended up in the watch fobs of Elks Club members.

Western jewelry featuring the teeth is increasingly popular. Collecting enough teeth for a dress would take a lifetime of hunting for an entire family, said Franklin Plenty Hoops, one of Winona’s three sons.

“Before, the white hunters would just give the teeth to me,” he said. “Now they know they can sell them.”

Plenty Hoops has tragedy to thank for many of her skills.

She was born only 40 years after the Battle of Little Big Horn. But a generation had already passed since her tribe left its nomadic ways for life on a reservation. Many of the traditions and skills were beginning to be forgotten in this harsh new world.

One winter when Plenty Hoops was very young, her mother died.

The following fall, her father, Bill Yellowtail, sent her two older sisters to boarding school. Plenty Hoops and her brother were too young. They went to live with their grandparents.

She used to spend afternoons riding horse with her grandfather, White Man Runs Him, who was a scout for Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer. Her grandmother, who didn’t speak a word of English, taught Plenty Hoops the traditional ways.

“She was one of the last ones who roamed,” Plenty Hoops said.

Plenty Hoops was sewing her own moccasins when she was 12. “You had to learn how to do it or you did without.”

After White Man Runs Him died in 1929, Plenty Hoops lived with family friends and relatives. There are no Crow orphans, she said, but that doesn’t mean it was an easy childhood.

She married at 16. Even for those days, 16 was young for a bride, Plenty Hoops said. But she wanted a family and a home. She wore an elk-teeth dress at her wedding.

|

A bride’s dress uses no set number of elk teeth. But, a lot of ivory is a sign of wealth and status. This was especially true when elk were hunted with bow and arrow.

Even with gunpowder, collecting enough ivories – at least 400 for a respectable gown – was not an easy task.

Elk have Billings business man Tom Meyers to thank for their dental preservation.

Every month Meyers creates about 15,000 elk canine teeth out of a composite plastic resin. Depending on their size, the teeth sell for about $16 per 100 from Meyer’s business, Buffalo Chips Indian Arts & Crafts, 327 S. 24th St. W.

“We sell them all over the nation, even Europe,” Meyers said. “There ain’t many hunters that are good enough to get enough real teeth anymore. Not even if they steal each other’s elk.”

The teeth are snow white when they come out of the mold. Meyers soaks some of the teeth in tea to replicate a natural ivory color. The root is then dyed with shoe polish. It costs about $100 to outfit a dress with enough fake elk teeth. Real teeth cost about $10 each.

Meyers guessed that only 10 or 12 dresses exist that are entirely adorned with real elk ivory. Most of these are in museums, he said.

Although Plenty Hoops has made dresses using real elk teeth, the last one she made was her daughter’s about 50 years ago. It was stolen. She doesn’t remember the exact date, but it was probably decades ago, she said.

|

In recent years, Plenty Hoops has been making Indian dolls, which sell for about $1,000 per couple. The dolls are completely handmade, including their buckskin heads.

She spent months agonizing over how to create realistic-looking heads, she said. Finally, a boy came to her in a dream one night and showed her the way.

She’s made about 15 doll couples. One set is owned by the Smithsonian Institution. Another set has hair from her own head.

“I should have charged more for that,” she said.

Plenty Hoops made her most recent elk-teeth dress about 15 years ago. She started it with 2-1/2 yards of trade cloth from England – at $32 per yard – and hundreds of shiny, white, plastic elk teeth.

She dyed the teeth herself, then spent about three days hand-stitching them to the cloth. Twelve real elk teeth were stitched to the front and back of the dress just below the collar, which is also framed by Plenty Hoops’ own beadwork.

The inside of the garment is backed with soft calico.

The dress is heavy – not unlike the heft of a thick, wool blanket. Hundreds of elk teeth gently tap the fabric when the person wearing the dress moves.

Plenty Hoops lost the ability to thread a needle in fall.

But her closet is still full of her handmade clothing, and she continues to wear only her own creations. Only about 10 Crow women remain who continue to make and wear their own clothes, she said.

On most days, Plenty Hoops wears a long calico dress. Around her waist, she keeps a thick, leather belt with a square pouch attached to the front. Her long, dark hair is tied into tight pony tails.

The only things Plenty Hoops doesn’t make are her hosiery, shoes and belt. For most of her life, she not only made her own footwear, she even tanned the leather.

Minutes after a freshly killed elk was brought home, Plenty Hoops would begin working the hide.

First, she draped it over a pipe and scraped away bits of flesh. The hide was soaked in water overnight and flung over the pipe in the morning. Plenty Hoops would then scrape away the hair. The hide was washed and allowed to dry slightly.

Bacon grease was rubbed into both sides. Then the hide was soaked again in water. Then it was stretched.

“Sometimes you’d have to do it two or three times to get it soft,” Plenty Hoops said.

Plenty Hoops’ self-reliance doesn’t stop with clothing.

She also makes her own medicines, using ancient family recipes. In a dining room cupboard, she keeps coffee cans full of pungent-smelling herbs, lichens and reeds. Everything is collected from local sites, she said.

“We live so close to nature,” she said. “Even now, we still do.”

One mixture cures cold and fever blisters in the mouths of babies. The herbs are charred, cooled, then gently placed in a baby’s mouth. The child quickly falls asleep and wakes without the blister, she said.

Another medicine cures bladder infections. Another cures not only diarrhea, but also constipation. “It works both ways,” she said.

Visitors come to her small home about every other day seeking help, she said.

“There’s a lot of us who still depend on Indian medicine,” she said.

Researchers have asked Plenty Hoops for the recipes. She has always refused.

The cures aren’t meant for profit, she said. Her typical payment is a carton of cigarettes, a box of candy, a handkerchief and a pair of socks.

Plenty Hoops’ sister had medicine for ulcers. She died in a car wreck.

“The medicine is lost now forever,” Plenty Hoops said.

In recent years, Plenty Hoops has begun working to spread her wisdom to her five children and dozens of grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

The Apsaalooke have spent the last 125 years trying to survive in an often unkind world. It would be a shame for their central traditions to be lost, she said.

Plenty Hoops’ dress- and doll-making skills have been passed on to her two daughters and her many granddaughters. “They’re all doing real nice work now,” she said.

Her daughter, Merle Jean Harris, of Hardin, said she is now taking over her mother’s remaining work.

Harris spends many of her evenings working on beadwork and sewing projects.

“I’m doing everything that she did,” Harris said. “She’s taught me all I know to do, except how to tan hides. I don’t want to learn how to tan hides.”

After receiving a Montana Folk and Traditional Arts Fellowship in 1994, Plenty Hoops also began teaching traditional Crow women’s handiwork to a women’s group on the reservation.

“Now, even little girls are doing it,” Plenty Hoops said. “We kept everything alive.”

Source:

James Hagengruber can be reached at 657-1232 or at jhagengruber@billingsgazette.com.

Copyright © The Billings Gazette