Ernest Spybuck (January 1883 – 1949), a.k.a. Mathkacea or Mahthela, often spelled his first name Earnest. He was born on the Potawatomi-Shawnee Reservation near Tecumseh, Oklahoma, to the White Turkey Band of the Absentee Shawnee, of the Rabbit clan. His parents were Peahchepeahso and John Spybuck.

Ernest Spybuck Biography

Earnest Spybuck began painting at around the age of six, but for most of his adult life he was occupied as a farmer, rather than as a professional artist. As late as 1938 he still relied on farming as his primary income. He spent his entire life in the area that became Pottawatomie County.

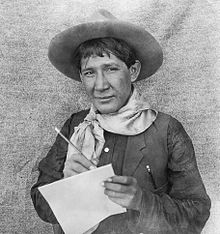

Absentee-Shawnee artist Ernest Spybuck,

Absentee-Shawnee artist Ernest Spybuck,

circa 1910. Public domain photo.Spybuck attended school at the Boarding School in Shawnee, Oklahoma and at Sacred Heart Mission in south-central Oklahoma, but his education never went beyond the McGuffey’s Third Reader. For the most part, he was self-taught.

According to his teacher at the Shawnee Boarding School, when he was eight years old, Spybuck would do nothing but draw and paint pictures with subjects drawn from his life.

At the age of 19, Spybuck married his wife Anna, and eventually the couple had three children.

He belonged to a large and influential family within the Absentee Shawnee Nation where he was an active member of the community and became a Peyote leader when the Native American Church was first adopted by Shawnee people. He died in 1949 at the age of 66 and was buried in a family plot near his home on Indian allotment land.

The Art of Ernest Spybuck

His patron was anthropologist M. R. Harrington, who was to feature Spybuck’s work in several ethnographic volumes that included material on the Shawnee and the Delaware. Harrington’s interest in the young artist was driven by Spybuck’s drawing ability and his interest in portraying scenes of contemporary tribal life.

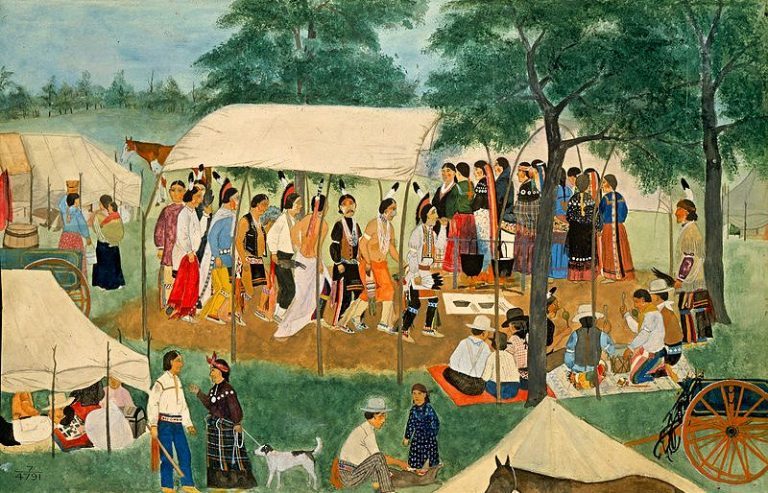

Buffalo Dance by Ernest Spybuck, 1918. Click on image to enlarge. The original was

Buffalo Dance by Ernest Spybuck, 1918. Click on image to enlarge. The original was

commissioned by Museum of the American Indian staff before 1918 and became part

of the collections of the National Museum of the American Indian, part of the Smithsonian.

This falls under institutional ownership, and in turn, because of the federal funding is in

the Public Domain.At the time, Harrington was collecting specimens and researching the tribes of the area for the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. His assistant brought Spybuck to his office, where he was able to examine the young man’s “unsophisticated” drawings. He appreciated the detailed accuracy of the equipment and dress depicted, and engaged him to create watercolors of ceremonies and social life of the tribes in the vicinity.

Spybuck produced watercolors for Harrington through 1921, and Harrington used some of them in a couple of monographs published by the Heye Foundation. Harrington also interviewed Spybuck for a work on the Shawnee that he never published, but he deposited his notes and Spybuck’s paintings with the Museum of the American Indian, which is now the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

One reviewer discounts the influence of Harrington’s patronage, claiming that Spybuck was already committed to depicting daily reservation life at their meeting and that his art matured along with his involvement with his local community, which included participating in the social activities and ceremonies that interested ethnographers.

Spybuck told Harrington that he preferred painting cowboys, livestock, and range scenes, but through Harrington’s patronage, Spybuck’s style evolved, particularly in his choice of subjects and the way he painted them.

His style was naïve and representational, featuring local scenes of ceremonies, games, social gatherings, and home life that he was familiar with and often participated in. His style recalled Plains flatstyle representative art that often identified individuals by depicting details of dress and accoutrement, but he took the representational depiction of the figures and setting in a new direction that was uniquely his own.

His “documentary realism” gave meticulous attention to dress, accouterments, and gesture, set in a simplified three-dimensional setting with well-defined foreground and background. He developed his own unique techniques, such as painting a cross-section “window” in a tipi or lodge where a ceremony would take place to show the activity inside, while also showing the landscape and time of day outside.

In Western European terms, Spybuck’s style might be called naïve art, but his works differs from most naïve artists’ due to the influence of ethnographic patronage that guided his choice to include certain details and an infusion of a sense of humor and personality. His scenes can provide subtle hints of attitudes and personalities of individual people and often include whimsical details on the periphery that contrast with the central activities.

Like Harrington, other reviewers recognize that Spybuck possessed a remarkable talent, but it often served a practical purpose in the domain of ethnography. His paintings served as illustrations for numerous anthropological writings.

Dobkins calls this practice autoethnography, in which the artist or writer assimilates the techniques of ethnographers to create representations of themselves and their cultures, with the implication of an asymmetrical power relationship between the ethnographer patron and the Native artist.

Other reviewers recognize Spybuck as an Indian artist who is a recorder and preserver of traditional practices in the midst of social change.

In Spybuck’s lifetime, works by Native American artists were just beginning to become exhibited as art rather than as ethnographic specimens.

In addition to having his art published in many books on American Indian cultures, several museums purchased his work for their collections. He was commissioned to produce murals for the Creek Indian Council House and Museum in Okmulgee, Oklahoma and at the Oklahoma Historical Society Museum in Oklahoma City. During his life his work was exhibited at the Museum of the American Indian in New York City and at the American Indian Exposition and Congress in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Collections of Earnest Spybuck Art

Collections of his work can be found today at:

- Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art, Shawnee, Oklahoma (home county to Spybuck)

- National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

- Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

- Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

- Oklahoma Historical Society Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

- Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, Norman, Oklahoma