AUTHOR: Joe S Sando, Jemez Pueblo

Six months of every year, the kachinas resided in the mountains to the west, where they could be seen as cloud banks gathering

above the peaks.

Then shortly after the winter solstice, they would return to the pueblo.

Summoned in secret kiva ceremonies, the kachinas arrived through the sipapu hole in the floor to act as intermediaries between the spirit realm and the world of humans.

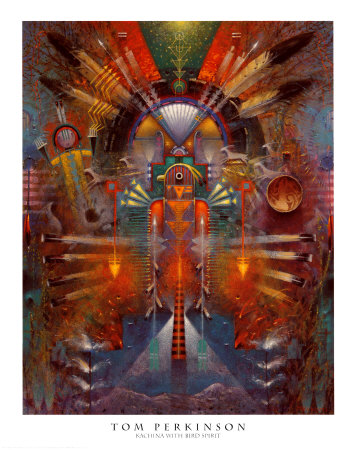

Kachina with Bird Spirit

Buy This Art Print At AllPosters.com

Find out how you can use this image for FREE.

During their stay the kachinas became the center of the pueblo’s ceremonial life.

On important occasions the men of the kachina

society, gloriously masked and costumed would emerge from the kivas and pour into the village square to dance and chant.

As each dancer performed, he would receive the spirit of the kachina he represented and so acquire the power to send prayers to the deities.

One of the kachinas’ tasks was to maintain discipline among the pueblo’s children and to instruct them in religious matters.

Each boy and girl at an early age received a wooden kachina doll, called a tithu in Hopi, carved from cottonwood root by the men of the kiva and given out during the dances.

When children were good, the kachinas would leave them presents. But should they misbehave, a kachina would appear, brandishing a yucca whip or cottonwood switch, and treat them to the fright of their young lives.

Some observers have said that the Pueblo ‘dance’ all the year round. This may be true, and was more the case in the past, since the ceremonial calendar covers the whole year.

Through dance and song one can realize a sense of rebirth and rejuvenation.

During the February Bean Dance festival, boys eight or nine years of age were assembled in the kiva, where the Kachina Chief

recited the creation story.

Suddenly, with a terrifying cry, other kachinas entered, carrying whips. Each boy received four

memorable lashes, after which gifts of sacred feathers and cornmeal were presented.

Then, after further ceremony and a sumptuous feast, the kachinas peeled off their masks-showing themselves to be men of the village.

Then began the serious business of instructing the children in the moral and spiritual truths of Pueblo life.

In the 1600’s the Spanish, in an effort to stamp out “devil worship,” forbade kachina dances, filled kivas with sand, and burned every mask, prayer stick, and effigy they could lay their hands on.

Eventually most Apache groups adopted a variation of the Pueblo kachinas-a population of benevolent beings they called gaan, the mountain spirits.

Intermediaries between humans and the higher powers, the gaan protected people and could be summoned from their homes inside the sacred mountains when needed.

On such occasions, usually rituals to cure the sick or mark the onset of a girl’s puberty, the mountain spirits were represented by specially trained and costumed dancers.

Even today, powerful sacred beings arrive at the Pueblo villages when summoned.

Men representing the kachinas, or cloud spirits, emerge masked and costumed to participate in line dances and other rites that can last for days.

Once invoked, the kachinas may bring rain and prosperity. In adition, impudent clown figures called koshares add leavity to the occasion while at the same time illustrating the folly of moral indiscretion.

Feasts are prepared and shared among villagers, while the kachinas give away dolls made in their likenesses to teach children the ways of the spirit world.