Over the past few years, the Columbia River has been blessed with record returns of fall chinook, coho and sockeye — returns the region hasn’t seen since Bonneville Dam was completed in 1938. This progress was neither easy nor haphazard. Over the last 40 years, a coalition of tribal, federal and state agencies worked together to reverse salmon declines.

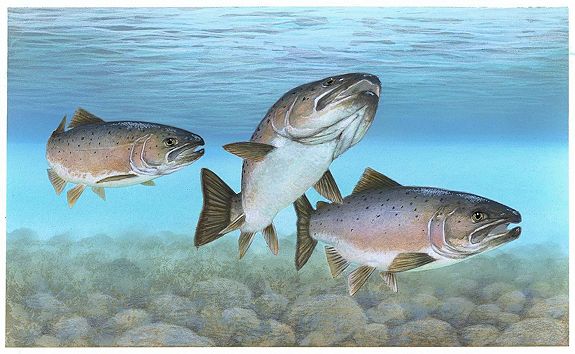

Photo Credit: Timothy Knepp, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Contrary to claims made by a few salmon interest groups, the Columbia Basin, while still facing many challenges, is home to world leaders in salmon management. Columbia River stocks provide the backbone for fisheries from Idaho all the way to southeast Alaska.

A recent Oregonian editorial poses a number of questions about the use of hatcheries in Columbia Basin salmon recovery. While some of the questions merit discussion, most stem from reactions to a sensationalized press release about the research and not from the Oregon State University research findings. The attention-grabbing release betrayed the actual research and mischaracterized the study’s conclusions. A fair review of the OSU research supports, not contradicts, what the tribes have been arguing for decades: Hatcheries can be an effective tool for increasing fish recovery and can be managed to minimize impacts on wild fish.

In the past, nearly all Pacific Northwest hatcheries were operated solely to provide salmon for fisheries with no regard to effects on wild populations. Fortunately, hatchery practices have advanced and evolved. The Yakama, Umatilla, Warm Springs and Nez Perce tribes called for hatchery reform in 1982, realizing that appropriately managed hatcheries can make the difference between empty rivers and healthy runs of salmon. These hatcheries — designed for the needs of the fish as a natural resource rather than the needs of humans for an economic and recreational source — represent a significant change in approach to help restore wild salmon populations.

Today, the salmon raised in tribal recovery hatcheries play a pivotal role in rebuilding sustainable salmon populations that are capable of supporting carefully managed river and ocean fisheries.

We stand by our programs and their results:

• In 1990, only 78 natural-origin (wild) Snake River fall chinook reached Lower Granite Dam. The run was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Last year, over 20,000 salmon reached the dam, thanks to restoration efforts begun in 1995 by the Nez Perce Tribe to avert the impending catastrophe. The Nez Perce success is the result of carefully supplementing wild stocks with well-managed hatchery fish. Initially opposed to the effort, state and federal agencies are now working cooperatively with the tribes on a long-term rebuilding program that is making progress towards de-listing the run in the next few years while providing benefits to all fishers.

The Umatilla River’s spring chinook population was extirpated in the early 1900s and water levels ran dangerously low. The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation worked with Umatilla Basin stakeholders to develop a comprehensive restoration approach that included flow enhancement, fish passage improvement, stream habitat enhancement and hatchery reintroduction/supplementation. By the late 1980s, fish began to return and runs have been healthy enough to support both a tribal and non-tribal fishery for the past 20 years.

In 2012, The Oregonian reported on the landscape-shifting research of the Nez Perce Tribe’s Johnson Creek supplementation program for spring chinook. Results from this study demonstrated that a carefully managed hatchery can prevent extinction and help rebuild natural abundance but can do so with minimal impacts to the natural population.

The region must recognize that the Columbia Basin does not have poor productivity because of hatcheries. Rather, we have hatcheries because of poor productivity. The Columbia Basin is no longer a wild, fully connected, healthy and whole ecosystem from the river mouth to the highest headwaters. The effects of the man-made alterations made to meet human needs have been almost more than the salmon could handle. We look forward to the day when salmon no longer need human intervention to maintain healthy, wild, self-sustaining populations.

Until then, using hatcheries as a recovery tool, together with habitat improvements, dam management priority changes and responsible fishery coordination, we can help these fish along until they can handle it themselves.

About the Author:

Jeremy Red Star Wolf is chairman of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission.