At the beginning of the 1830s, nearly 125,000 Native Americans lived on millions of acres of land in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina and Florida–land their ancestors had occupied and cultivated for generations. By the end of the decade, very few natives remained anywhere in the southeastern United States.

Working on behalf of white settlers who wanted to grow cotton on the Indians’ land, the federal government forced them to leave their homelands and walk hundreds or even thousands of miles to a specially designated “Indian territory” across the Mississippi River (where Oklahoma is today). This difficult and sometimes deadly journey is known as the Trail of Tears.

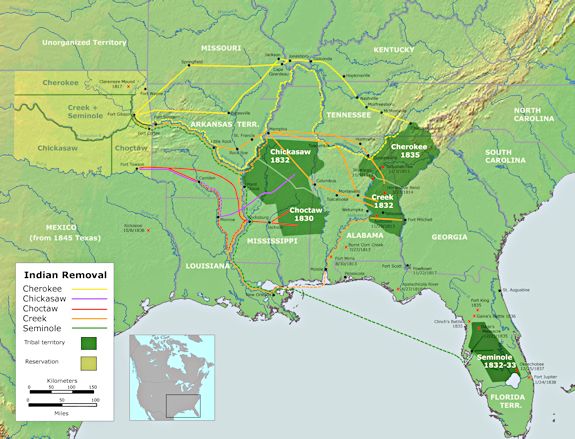

Map of United States Indian Removal, 1830-1835. Oklahoma is depicted in light yellow-green. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia. Click to Enlarge.

When many people think of the Native American Trail of Tears, they think of the Cherokee tribe, but there were other tribes who also had a “Trail of Trears.” All of the “Civilized Tribes” were removed.

The “Indian Problem”

White Americans, particularly those who lived on the western frontier, often feared and resented the Native Americans they encountered. To them, American Indians seemed to be an unfamiliar, alien people who occupied land that white settlers wanted (and believed they deserved).

Some officials in the early years of the American republic, such as President George Washington, believed that the best way to solve this “Indian problem” was simply to “civilize” the Native Americans. The goal of this civilization campaign was to make Native Americans as much like white Americans as possible by encouraging them convert to Christianity, learn to speak and read English, and adopt European-style economic practices such as the individual ownership of land and other property (including, in some instances in the South, African slaves).

In the southeastern United States, many Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek and Cherokee people embraced these customs and became known as the “Five Civilized Tribes.”

But their land, located in parts of Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, Florida and Tennessee, was valuable, and it grew to be more coveted as white settlers flooded the region. Many of these whites yearned to make their fortunes by growing cotton, and they did not care how “civilized” their native neighbors were.

They wanted that land and they would do almost anything to get it. They stole livestock; burned and looted houses and towns; and squatted on land that did not belong to them.

State governments joined in this effort to drive Native Americans out of the South. Several states passed laws limiting Native American sovereignty and rights and encroaching on their territory.

In a few cases, such as Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the U.S. Supreme Court objected to these practices and affirmed that native nations were sovereign nations “in which the laws of Georgia [and other states] can have no force.” Even so, the maltreatment continued. As President Andrew Jackson noted in 1832, if no one intended to enforce the Supreme Court’s rulings (which he certainly did not), then the decisions would “[fall]…still born.”

Southern states were determined to take ownership of Indian lands and would go to great lengths to secure this territory.

The Trail of Tears Begins with Choctaw Indian Removal

Andrew Jackson had long been an advocate of what he called “Indian removal.” As an Army general, he had spent years leading brutal campaigns against the Creeks in Georgia and Alabama and the Seminoles in Florida–campaigns that resulted in the transfer of hundreds of thousands of acres of land from Indian nations to white farmers.

As president, he continued this crusade. In 1830, he signed the Indian Removal Act, which gave the federal government the power to exchange Native-held land in the cotton kingdom east of the Mississippi for land to the west, in the “Indian colonization zone” that the United States had acquired as part of the Louisiana Purchase.

The law required the government to negotiate removal treaties fairly, voluntarily and peacefully. It did not permit the president or anyone else to coerce Native nations into giving up their land. However, President Jackson and his government frequently ignored the letter of the law and forced Native Americans to vacate lands they had lived on for generations.

In the winter of 1831, under threat of invasion by the U.S. Army, the Choctaw became the first nation to be expelled from its land altogether.

Nearly 17,000 Choctaws together with 1000 slaves made the move to what would be called Indian Territory. After ceding nearly 11,000,000 acres (45,000 km2), the Choctaw emigrated in three stages: the first in the fall of 1831, the second in 1832 and the last in 1833. This period included the devastating winter blizzard of 1830-31 and the cholera epidemic of 1832. They made the journey to Indian territory on foot (some “bound in chains and marched double file,” one historian wrote) and without any food, supplies or other help from the government. About 2,500 to 6,000 people died along the way. It was, one Choctaw leader told an Alabama newspaper, a “trail of tears and death.”

The Choctaw removal continued throughout the 19th century. In 1846 another 1,000 Choctaw were removed, and in 1903 another 300 Mississippi Choctaws were persuaded to move to the Nation in Oklahoma. Only 1,665 Choctaws remained in Mississippi.

The Creek Trail of Tears

After the War of 1812, some Muscogee leaders such as William McIntosh signed treaties that ceded more land to Georgia. The 1814 signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson signaled the end for the Creek Nation and for all Indians in the South. Friendly Creek leaders, like Selocta and Big Warrior, addressed Sharp Knife (the Indian nickname for Andrew Jackson) and reminded him that they keep the peace. Nevertheless, Jackson retorted that they did not “cut (Tecumseh’s) throat” when they had the chance, so they must now cede Creek lands. Jackson also ignored Article 9 of the Treaty of Ghent that restored sovereignty to Indians and their nations.

“Jackson opened this first peace session by faintly acknowledging the help of the friendly Creeks. That done, he turned to the Red Sticks and admonished them for listening to evil counsel. For their crime, he said, the entire Creek Nation must pay. He demanded the equivalent of all expenses incurred by the United States in prosecuting the war, which by his calculation came to 23,000,000 acres (93,000 km2) of land.” – Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson

Eventually, the Creek Confederacy enacted a law that made further land cessions a capital offense. Nevertheless, on February 12, 1825, McIntosh and other chiefs signed the Treaty of Indian Springs, which gave up most of the remaining Creek lands in Georgia.[40] After the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty, McIntosh was assassinated on May 13, 1825, by Creeks led by Menawa.

The Creek National Council, led by Opothle Yohola, protested to the United States that the Treaty of Indian Springs was fraudulent. President John Quincy Adams was sympathetic, and eventually the treaty was nullified in a new agreement, the Treaty of Washington (1826).

The historian R. Douglas Hurt wrote, “The Creeks had accomplished what no Indian nation had ever done or would do again — achieve the annulment of a ratified treaty.” However, Governor Troup of Georgia ignored the new treaty and began to forcibly remove the Indians under the terms of the earlier treaty. At first, President Adams attempted to intervene with federal troops, but Troup called out the militia, and Adams, fearful of a civil war, conceded. As he explained to his intimates, “The Indians are not worth going to war over.”

Although the Creeks had been forced from Georgia, with many Lower Creeks moving to the Indian Territory, there were still about 20,000 Upper Creeks living in Alabama. However, the state moved to abolish tribal governments and extend state laws over the Creeks. Opothle Yohola appealed to the administration of President Andrew Jackson for protection from Alabama; when none was forthcoming, the Treaty of Cusseta was signed on March 24, 1832, which divided up Creek lands into individual allotments.

Creeks could either sell their allotments and receive funds to remove to the west, or stay in Alabama and submit to state laws. The Creeks were never given a fair chance to comply with the terms of the treaty, however. Rampant illegal settlement of their lands by Americans continued unabated with federal and state authorities unable or unwilling to do much to halt it.

Further, as recently detailed by historian Billy Winn in his thorough chronicle of the events leading to removal, a variety of fraudulent schemes designed to cheat the Creeks out of their allotments, many of them organized by speculators operating out of Columbus, Georgia and Montgomery, Alabama, were perpetrated after the signing of the Treaty of Cusseta.

A portion of the beleaguered Creeks, many desperately poor and feeling abused and oppressed by their American neighbors, struck back by carrying out occasional raids on area farms and committing other isolated acts of violence. Escalating tensions erupted into open war with the United States following the destruction of the village of Roanoke, Georgia, located along the Chattahoochee River on the boundary between Creek and American territory, in May 1836.

During the so-called “Creek War of 1836” Secretary of War Lewis Cass dispatched General Winfield Scott to end the violence by forcibly removing the Creeks to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. In 1836, the federal government drove over 15,000 Creeks from their land for the last time. Of those who set out for Oklahoma, 3,500 did not survive the trip.

Seminole Wars and Removal

The U.S. acquired Florida from Spain via the Adams–Onís Treaty and took possession in 1821. In 1832 the Seminoles were called to a meeting at Payne’s Landing on the Ocklawaha River. The treaty negotiated called for the Seminoles to move west, if the land were found to be suitable.

They were to be settled on the Creek reservation and become part of the Creek tribe, who considered them deserters; some of the Seminoles had been derived from Creek bands but also from other tribes. Those among the tribe who once were members of Creek bands did not wish to move west to where they were certain that they would meet death for leaving the main band of Creek Indians.

The delegation of seven chiefs who were to inspect the new reservation did not leave Florida until October 1832. After touring the area for several months and conferring with the Creeks who had already settled there, the seven chiefs signed a statement on March 28, 1833 that the new land was acceptable.

Upon their return to Florida, however, most of the chiefs renounced the statement, claiming that they had not signed it, or that they had been forced to sign it, and in any case, that they did not have the power to decide for all the tribes and bands that resided on the reservation. The villages in the area of the Apalachicola River were more easily persuaded, however, and went west in 1834.

On December 28, 1835 a group of Seminoles and blacks ambushed a U.S. Army company marching from Fort Brooke in Tampa to Fort King in Ocala, killing all but three of the 110 army troops. This came to be known as the Dade Massacre.

As the realization that the Seminoles would resist relocation sank in, Florida began preparing for war. The St. Augustine Militia asked the War Department for the loan of 500 muskets. Five hundred volunteers were mobilized under Brig. Gen. Richard K. Call. Indian war parties raided farms and settlements, and families fled to forts, large towns, or out of the territory altogether.

A war party led by Osceola captured a Florida militia supply train, killing eight of its guards and wounding six others. Most of the goods taken were recovered by the militia in another fight a few days later. Sugar plantations along the Atlantic coast south of St. Augustine were destroyed, with many of the slaves on the plantations joining the Seminoles.

Other warchiefs such as Halleck Tustenuggee, Jumper, and Black Seminoles Abraham and John Horse continued the Seminole resistance against the army. The war ended, after a full decade of fighting, in 1842. The U.S. government is estimated to have spent about $20,000,000 on the war, at the time an astronomical sum, and equal to $496,344,828 today.

Many Indians were forcibly exiled to Creek lands west of the Mississippi; others retreated into the Everglades. In the end, the government gave up trying to subjugate the Seminole in the Everglades and left fewer than 100 Seminoles in peace. However, other scholars state that at least several hundred Seminoles remained in the Everglades after the Seminole Wars.

As a result of the Seminole Wars, the surviving Seminole band of the Everglades claims to be the only federally recognized tribe which never relinquished sovereignty or signed a peace treaty with the United States.

Chickasaw Receive Compensation for Removal to Indian Territory

Resisting European-American settlers encroaching on their territory, the Chickasaw were forced by the US to sell their country in the 1832 Treaty of Pontotoc Creek and move to Indian Territory. Between 1832 and 1837, the Chickasaw would make further negotiations and arrangements for their removal.

Unlike other tribes who received land grants in exchange for ceding territory, the Chickasaw held out for financial compensation: they were to receive $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River. In 1836 after a bitter five-year debate within the tribe, the Chickasaw had reached an agreement to purchase land in Indian Territory from the previously removed Choctaw. They paid the Choctaw $530,000 for the westernmost part of their land. The first group of Chickasaw moved in 1837. For nearly 30 years, the US did not pay the Chickasaw the $3 million it owed them for their historic territory in the Southeast.

The Chickasaw gathered at Memphis, Tennessee, on July 4, 1837, with all of their portable assets: belongings, livestock, and enslaved African Americans. Three thousand and one Chickasaw crossed the Mississippi River, following routes established by the Choctaw and Creek. More than 500 Chickasaw died of dysentery and smallpox on the way to Indian Territory.

The Cherokee were the last to travel the Trail of Tears

The Cherokee people were divided. What was the best way to handle the government’s determination to get its hands on their territory? Some wanted to stay and fight. Others thought it was more pragmatic to agree to leave in exchange for money and other concessions.

In 1835, a few self-appointed representatives of the Cherokee nation negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, which traded all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi for $5 million, relocation assistance and compensation for lost property. To the federal government, the treaty was a done deal, but many of the Cherokee felt betrayed. After all, the negotiators did not represent the tribal government or anyone else.

“The instrument in question is not the act of our nation,” wrote the nation’s principal chief, John Ross, in a letter to the U.S. Senate protesting the treaty.

“We are not parties to its covenants; it has not received the sanction of our people.” Nearly 16,000 Cherokees signed Ross’s petition, but Congress approved the treaty anyway.

By 1838, only about 2,000 Cherokees had left their Georgia homeland for Indian territory. President Martin Van Buren sent General Winfield Scott and 7,000 soldiers to expedite the removal process.

Scott and his troops forced the Cherokee into stockades at bayonet point while whites looted their homes and belongings. Some were able to flee and hide in the mountains, and decendants of those Cherokee are known today as the Eastern Cherokee.

Those that were located were marched more than 1,200 miles to Indian territory. Whooping cough, typhus, dysentery, cholera and starvation were epidemic along the way, and historians estimate that more than 5,000 Cherokee died as a result of the journey.

By 1840, tens of thousands of Native Americans had been driven off of their land in the southeastern states and forced to move across the Mississippi to Indian territory. The federal government promised that their new land would remain unmolested forever, but as the line of white settlement pushed westward, “Indian country” shrank and shrank. In 1907, Oklahoma became a state and Indian territory was gone for good.