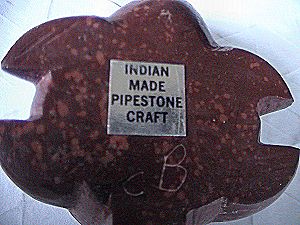

QUESTION: I have been researching a turtle I bought at a garage sale last weekend. The label reads “Indian Made Pipestone Craft.” It measures about 2 3/4 inches long and 2 inches across the shell. I do not feel right about selling it on ebay. I will if there isn’t an issue. Please let me know if I should contact someone who would want this back or if it is disrespectful to sell it.

Submitted by Elizabeth G.

ANSWER:

Hi Elizabeth,

This turtle effigy is what is known in the indian arts and craft trade as a fetish. Generally, native americans aren’t particularly offended if you sell fetishes, on ebay or otherwise, unless they are burial items taken from grave sites, which this one clearly isn’t, or if they have been used as a ceremonial object, which I would strongly doubt with this piece because it is clearly labled for the tourist trade. Selling a fetish, in general, is not considered offensive.

Traditional Fetishes

Traditionally, fetishes were made by the Pueblo tribes as personal ceremonial objects representing certain animals, and were believed to contain spirits of the animal they represented. They were believed to bring good luck, provide protection, lend endurance, or otherwise endow the owner with powers attributed to that specific animal. Another name for a fetish carving is an effigy. Some Pueblo tribes only carve one type of animal effigy and consider it taboo to carve others. For example, the Santo Domingo Pueblo only carves bird fetishes.

Traditionally, fetishes were made by the Pueblo tribes as personal ceremonial objects representing certain animals, and were believed to contain spirits of the animal they represented. They were believed to bring good luck, provide protection, lend endurance, or otherwise endow the owner with powers attributed to that specific animal. Another name for a fetish carving is an effigy. Some Pueblo tribes only carve one type of animal effigy and consider it taboo to carve others. For example, the Santo Domingo Pueblo only carves bird fetishes.

Today people from many indian tribes, and even non-indians make fetishes for tourists and collectors of art. They are usually thought of as an art object today, rather than a ceremonial item. Fetishes are mass produced in Arizona and New Mexico, and in countries like Mexico and the Philippines, as well as made by individual artists.

Many native american people are offended by this copying, or “appropriation” of their traditional arts. However, on the other hand, a lot of Indian people will buy these foreign or mass produced pieces themselves, sign them and say they made them themselves. So, just because it’s signed doesn’t particularly mean anything, unless you know it’s particular history, the background and reputation of the carver, and can document it, or you saw it made with your own eyes.

A very large number of the fetishes on the market today are mass produced commercially for the tourist trade, as I suspect this one was because of the little “Indian Made Pipestone Craft” plaque on the back. That tells me it was produced for the tourist trade and isn’t a ceremonial object and was never used as one.

Whether or not it was actually made by a federally recognized native american person would be open to debate, unless you have documented proof that leads back to the carver of this piece, which apparently you don’t. Catlinite comes from a quarry mine ceded to the Yankton Sioux tribe, but also used by other tribes for generations. That in itself doesn’t necessarily mean the fetish was carved by a member of the Sioux tribes, or even any indian tribe, because catlinite is often traded and sold in raw blocks to anyone who wants to buy it, and many fetish carvers are non-indians.

Whether or not it was actually made by a federally recognized native american person would be open to debate, unless you have documented proof that leads back to the carver of this piece, which apparently you don’t. Catlinite comes from a quarry mine ceded to the Yankton Sioux tribe, but also used by other tribes for generations. That in itself doesn’t necessarily mean the fetish was carved by a member of the Sioux tribes, or even any indian tribe, because catlinite is often traded and sold in raw blocks to anyone who wants to buy it, and many fetish carvers are non-indians.

Those markers that say an item is Indian Made can be purchased at most jewelry making supply houses or custom printed at any print shop. Selling items not made by federally recognized indians with the label “Indian Made” or “Indian Produced” is against the law and is a federal offense today, but it wasn’t prior to 1996, and it was a common practice to use these labels regardless of who made the item prior to that time. I don’t know how old this particular fetish is.

Even today, this law is largely unenforced due to lack of funding and is flagrantly abused in the indian arts and crafts industry. So, even though it is labled “Indian Made,” there is no guarantee that it is if you don’t know it’s specific history.

Catlinite is a sacred stone

What some native americans might object to is the material this fetish is made from, which is catlinite, commonly called pipestone because of it’s popularity in making the canupa, or pipe bowl. This catlinite material is quarried at only one place in the world: the Pipestone Quarry in Minnesota inside the Pipestone National Monument.

In most instances, native americans are usually only offended if you sell catlinite (pipestone) that is made into pipes, but some traditionalists object to any object made of catlinite being sold for profit or made into a non-ceremonial object.

While the Pipestone Quary is considered a native american sacred site, and some traditional Sioux people do object to the stone itself or ANY items made from the stone being sold, it is other members of their own tribes who are doing the selling. They even have a tourist gift shop near the quarry where you can buy all kinds of catlinite objects, including the sacred catlinite pipe bowls. This is a controversial practice, even among Indians, who can’t agree on what is proper protocol.

The Pipestone Legends

For centuries, tribes have gathered at the pipestone quarry to obtain the smooth rock they usually use to make pipes. The area was a neutral zone, where different groups came together in peace. It was said that if you approached the quarry and a light rain fell, this was a sign that you were permitted to enter. By the 1700s, native trade was so extensive that the distinctive red pipe bowls were found throughout large parts of North America.

Several legends tell of the origin of the distinctive red color. In Dakota Sioux tradition, the Great Spirit sent a flood to cleanse the earth, and the red pipestone (inya sa) that remains is the blood of the ancestors. As written by the explorer , author, and artist George Catlin, “the Great Spirit declared that the red stone was their flesh, that they were made from it, that they must all smoke to him through it, that they must use it for nothing but pipes–and as it belonged to all tribes, the ground was sacred, and no weapons must be used or brought upon it.”

Another legend attributes the red color to blood from a fierce battle. When the last two chiefs killed each other, the people would have been extinct, but three young women hid behind huge rocks nearby. These rocks are in a valley near the quarry and are known as the Three Maidens.

How the Pipestone Quarry became a National Monument

The 1858 Treaty of Washington DC promised to keep the quarry open to the Yankton Sioux “so long as they shall desire” but they had to give up 11 million acres in return for a reservation of 430,000 acres and some land surrounding the quarry. In their continuing effort to suppress and weaken native religions, missionaries convinced the government to exclude the Three Maidens from this tract of land.

In spite of the treaty, the 1870s saw a series of encroachments by white settlers. Though the Yankton’s rights were affirmed in the beginning, enforcement was lax due to legal battles and administrative delays. The Yankton were outraged when, in 1890 and 1891, plans were unveiled to build a railroad and an Indian school for other tribes on the quarry land.

In the legislative history introducing the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act, the congressional task force acknowledged that the government had deliberately planned the railroad construction to run through the sacred ledges which created the waterfalls of the quarry in order to “erase all traces of their former outlines and to render them useless for ceremonial purposes.” During this period, the government argued that the land did not belong to the Yankton, but to the government, which had reserved only quarry use for the Yankton by treaty.

It was under this cloud of uncertainty that the Yankton negotiated an agreement with the Secretary of the Interior under which they gave up all rights and interest in the Pipestone Reservation, retaining permission to camp and quarry on a 40-acre tract of their choosing, in exchange for $100,000 (plus 6% interest for previous encroachments) to be paid in cattle and cash. The United States agreed to maintain the area as a national park.

Ratification of this agreement was stalled because the question of whether or not the Yankton owned the quarry had not been resolved. In 1925, the Court of Claims upheld the Government’s contention that no compensation was due the Yankton since they never held title to the land. Then, the Supreme Court established that the Yankton did own the land and they ordered the Court of Claims to set its value. The Deficiency Appropriation Act of March 4, 1929, provided payment of $328,558.90, which resulted in the members of the tribe receiving $151.99 per person. This sale cleared the way for the establishment of Pipestone National Monument in 1937. The government agreed to protect the area and allow the Yankton to use the quarry.

The controversy over selling catlinite

While non-Indians are barred from quarrying at Pipestone, there are still disagreements about who has the right to quarry and sell pipes.

The Yankton Sioux, a federally-recognized tribe in South Dakota, feel that quarrying should be limited to specific ceremonial use and that pipes should not be sold under any circumstances. They are joined in this sentiment by Lakota elders and the National Congress of American Indians.

The Pipestone Native American community, an unrecognized group mostly descended from Dakota bands, has been living around Pipestone and quarrying for generations. They argue that the Yankton do not have the exclusive right to determine the protocol for use of the quarry, and that selling pipes is an acceptable contemporary variation on past customs of bartering.

The years 1987-1994 saw a major campaign by the Yankton Sioux asking the Pipestone community to “immediately vacate the Red Sacred Pipestone quarries.” The Yankton organized ceremonial runs and a Keepers of the Treasures convention to discuss the issue, raise awareness, and attract national attention.

Catlinite isn’t commonly used to make fetishes, mainly because it is a costly stone, it’s only mined at one place in the world that is off limits to non-indian miners, so it’s harder to come by, there is controversy surrounding it, and there are many cheaper alternatives that sell just as well. But, I have seen catlinite fetishes offerred for sale often enough to say that it isn’t an unusual practice. Pipe makers will sometimes use their smaller catlinite scraps that are too small for pipes, or which contain flaws that make them unsuitable for pipe bowls, to carve fetishes rather than waste the sacred stone.

What affects the price of a fetish

The value of a fetish depends on the detail of the workmanship, the ethnicity and artistic reputation of the carver, the size of the fetish, and the quality and type of stone used. The value of a fetish this size could be anywhere from $15-20 up to about $500.00 depending on these factors.

I don’t know who CB is, so I can’t tell you about the artist. The workmanship isn’t very detailed, and the size is smallish, but the stone used is less common than most. Unless CB belongs to a federally recognized tribe and has a reputation as a master fetish carver, (which it appears you can’t document at this point), I would guess you could probably get somewhere in the range of $20-45 for this fetish, should you choose to sell it, or perhaps a bit more if you find a collector who is specifically interested in a catlinite fetish.

FURTHER READING:

Pipestone Indian Shrine Association

Government sponsored site about Pipestone National Monument

A History of Pipestone National Monument

Little Feather Interpretive Center

Keepers of the Sacred Tradition of Pipemakers

Indian Art in Pipestone: George Catlin’s Portfolio in the British Museum

Native American Fetish Carvings of the Southwest

Building on a Borrowed Past: Place and Identity in Pipestone, Minnesota