Generally, native americans in what would become the United States and Canada didn’t have royalty such as kings, but there were rare exceptions. There were three Mohawk chiefs of the Iroquois Confederacy and a Mahican of the Algonquian peoples who were called Kings.

While these four Iroquois were not the first American Indians to visit England (Pocahontas had come in 1616), they were the first to be treated as heads of state.

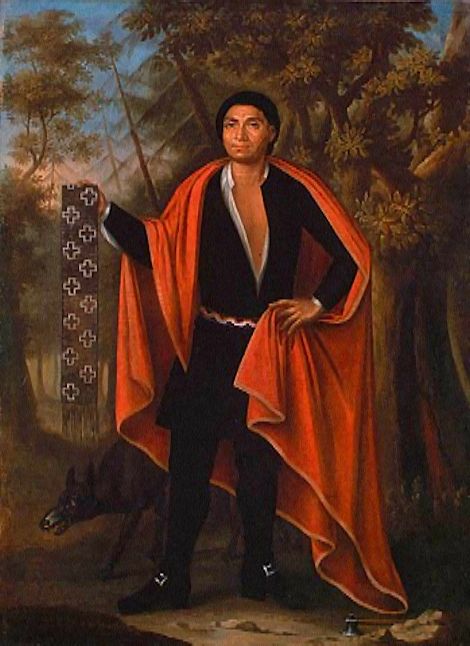

Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow or Sagayeathquapiethtow,

Mohawk King of Maguas, Painting by Jan Veresldt, 1710The three Mohawk kings were: Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow of the Bear Clan, called King of Maguas, with the Christian name Peter Brant (grandfather of Mohawk leader Joseph Brant); Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row of the Wolf Clan, called King of Canajoharie (“Great Boiling Pot”), or John of Canajoharie; and Tee Yee Ho Ga Row, meaning “Double Life”, of the Wolf Clan, also called Hendrick Tejonihokarawa or King Hendrick.

The Mahican chief was Etow Oh Koam of the Turtle Clan, mistakenly identified in his portrait as Emperor of the Six Nations. The Mohawk were one of the five original tribes in the Iroquois League but the Algonquian-speaking Mohican people were not part of the Iroquois Confederacy. Five chiefs set out on the journey, but one died in mid-Atlantic on the way to London.

The four Native American leaders visited Queen Anne in 1710 as part of a diplomatic visit organised by Pieter Schuyler, mayor of Albany, New York.

Peter Schuyler, a former mayor of Albany, a well to do fur trader, and a member of the New York Indian Commission; took five Mohawk chiefs, of the Five Nations of the Iroquois, to London, England in 1710. Schuyler wanted them to ask for assistance against their French enemies. This was a purely political move for Schuyler. Aid from the motherland (England) would greatly improve his position in the colonies. The Iroquois held Schuyler in high regard. He was their special intermediary with the colonial government.

The Four Kings in London were treated as royalty

The Four Kings were received in London as diplomats, being transported through the streets of the city in Royal carriages, and received by Queen Anne at the Court of St. James Palace. Queen Ann reigned from 1702-1714,and was the successor of William III and her sister, Mary II.

Many nobles competed for the privilege of entertaining these “Four Indian Kings” as they were called, while they were in London.

It was said that the kings were almost two meters tall and had an imposing bearing and splendid physiques. The British court was still mourning the death of Prince George of Denmark, Queen Anne’s husband and King.

The four “American kings” were fêted by society. They visited the Tower of London and St. Paul’s Cathedral. They saw a performance of Shakespeare’s Macbeth at the Haymarket Theatre, and attended the Royal Opera. They also attended a “trial of skill with sword” between two fighting Englishmen and visited the Cockpit Royal, where they witnessed the “Royal Sport” of cockfighting firsthand.They also witnessed bear fights, and wrestling matches.

Gifts from the Queen

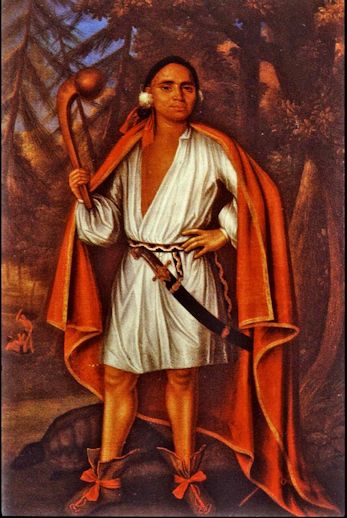

Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row” John of Canojaharie (“Great Boiling Pot”)

of the Mohawk wolf clan. Painting by Jan Veresldt, 1710Queen Anne commissioned Court painter, Jan Verelst, to paint the portraits of the Four Kings. Queen Anne commissioned Court painter, Jan Verelst, to paint the portraits of the Four Kings. She also ordered the construction of a new fort and chapel, called Fort Hunter, along the Mohawk River. Queen Anne provided missionaries from the Church of England and she patronized the Mohawk mission.

The missionaries devised a system of writing in the Mohawk language and religious literature was translated into Mohawk. Cheif Hendrick was said to be one of the most faithful.

In addition to requesting military aid for defence against the French, the chiefs asked for missionaries to offset the influence of French Jesuits, who had converted numerous Mohawk to Catholicism.

Queen Anne informed the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Tenison. A mission was authorized, and Mayor Schuyler had a chapel built the next year at Fort Hunter (located near the Mohawk “Lower Castle” village).

Queen Anne sent a gift of a silver Communion set and a reed organ. The Mohawk village known as the “Lower Castle” became mostly Christianized in the early 18th century, unlike the “Upper Castle” at Canajoharie further upriver. No mission at the latter was founded until William Johnson, the British agent to the Iroquois, built the Indian Castle Church in 1769.

A large collection of historical documentation survives that recounts their memorable visit including numerous versions of their speech to Queen Anne, other published accounts of their visitation, some 30 portraits of the Kings in the form of engravings and miniatures, and four portrait oil paintings.

These oil paintings are important because they accurately depict perhaps for the first time in Western history the facial and body tattoo of the Mohawk and neighboring Mahican.

Iroquois and Mahican Tattoos

According to Jesuit documents, Iroquois and Mahican tattoo designs were first stenciled on the skin and then pricked into the flesh with trade needles or little bones until the blood flowed. Then, crushed charcoal (or sometimes red cinnabar) was vigorously rubbed into the open wounds.

Iroquois women, however, were rarely tattooed. But when they did, the purpose was usually medicinal, as a remedy to cure toothache or rheumatism. According to the Jesuit priest Lafitau, these women “content themselves with having a little branch of foliage traced along the jaw. They claim that the nerve by which the humour flows over the teeth is thus pricked, so that it can no longer fall there and that thus they cure the pain by going to the source of the ill.”

Iroquois men tattooed to signify achievement on the field of battle, including cross-hatches on the face to record successful military expeditions, or other small marks on the thighs to indicate the number of enemies killed.

According to a Jesuit relation of 1663, one Iroquois war-chief bore 60 tattoo marks on one thigh alone! Many other markings, which have lost their meaning and function, were placed upon the face and body, although some were probably totemic.Nevertheless, nearly all Iroquois men’s tattoos were distinct to them.

According to the account book of Dutch trader Evert Wendell dated August 13, 1706, a young Seneca, living in Canosedaken, his name Tan Na Eedsies, visited Wendell in Albany, New York and completed his transaction by drawing a pictograph next to his order. This drawing identified Tan Na Eedsies, and the tattooed patterns on his face, neck, and chest were considered equivalent to his personal signature.

Of the four Indian Kings, only three were actually tattooed. Two tattooed sachems were Mohawk (Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row and Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow) and one (Etow Oh Koam or John) was Mahican, a tribe that was loosely allied to the Five Nations Confederacy.

In each portrait, the clan totem of each King (wolf, bear, turtle) is represented standing near the base of the canvas. Moreover, all three Kings are presented with their weapons; these symbols attest to their success and prowess on the field of battle. The Kings wore black breeches, vests, and stockings and over this they wore a scarlet cloak trimmed with gold.

The Mohawks made a sensation all dressed in exotic apparel. The red cloaks were made for the chiefs upon their arrival and were gifts from Queen Anne.

The portrait of Etow Oh Koam is especially significant because it is the only known portrait of an 18th century Mahican chief.

These paintings hung in Kensington Palace until 1977 when Queen Elizabeth II had them relocated to the National Archives of Canada. She unveiled them in Ottawa.

Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow (1710) of the Mohawk Bear clan, had his portrait labelled “King of Maguas.” He is shown holding a musket. He is is depicted with elaborate tatoos.

He was the grandfather of Joseph Brant. Joseph’s grandfather was Catholic.

Sagayeathquapiethtow son’s name was Tehowaghwengaraghkwin (“a man taking off his snowshoes”), whose Christian name was Peter Brant. Peter was Joseph Brandt’s father and the hereditary Tekarihoga, the leading sachem of the Mohawks.

Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row or John of Canojaharie (“Great Boiling Pot”) of the Mohawk wolf clan is shown holding a bow while a quiver of arrows is on the ground, and his portrait is labelled “King of Canojaharie.”

Behind him is a wolf, representing his clan.

Canajoharie was located on the south side of the Mohawk River, thirty miles upstream from the lower castle called Tionderoga, which was located next to Fort Hunter.

Tee Yee Ho Ga Row or Hendrick Tejonihokarawa, also

known as Hendrick Peters or King Hendrick. Painting by

Jan Veresldt, 1710.“Tee Yee Ho Ga Row” meaning “Double Life” of the wolf clan is shown holding a wampum belt. He was also known as Hendrick Tejonihokarawa or King Hendrick (c.1660-1735), or Hendrick Peters, a Mahican-Mohawk leader.

He advanced to leadership among the Mohawks after his adoption into the Wolf Clan. (There were Mahicans living among the Mohawks.) King Hendrick was a Christian and he was said to have been over six feet tall.

He lived at Tiononderoge, the Lower Castle, closer to the English base in Albany.

Until the late 20th century, Hendrick’s biography was confused with a younger Mohawk leader given the same first name in baptism, Hendrick Theyanoguin, (c. 1691 – September 8, 1755) (also known as Hendrick Peters). The latter was a member of the Bear Clan (an important difference, as shown by the historian Barbara Silvertsen) and based at Canajoharie or the Upper Mohawk Castle in colonial New York.

He was a Speaker for the Mohawk Council. This Hendrick formed a close alliance with Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian affairs in North America.

It was the younger Hendrick Theyanoguin, at the age of 70, who in 1755 led 300 warriors to fight against the French alongside the English at the Battle of Lake George. That Hendrick was killed in the conflict at a battle site near Lake George in the Adirondacks.

“Emperor of the Six Nations” Etow Ch Koam” or Nicholas,

Mahican of the Turtle Clan. Painting by Jan Veresldt, 1710Etow Ch Koam or Nicholas was a Mahican of the Turtle clan. He is holding a ball-headed war club and an English dress sword. This portrait is erroneously labelled “Emperor of the Six Nations” of the Upper Hudson River Valley.

The Fate of the Indian Kings and Five Nations

America’s Tattooed Indian Kings returned to Boston on July 15, 1710. Although the sachems had witnessed “the Grandeur, Pleasure and Plenty” of the British nation, Brant died shortly before they were to return from London, according to one source. Another says he died shortly after they returned.

Both Nicholas and John faded into obscurity. Nothing more is known of them.

In the summer of 1711, however, a massive British military expedition involving some 12,000 American colonists and 800-odd Native Americans from the Five Nations did set sail from Boston in 60 transports and 9 man-of-war.

Their destination was the French stronghold of Quebec; the palisaded city that was the key station to the important trade routes on the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes.

Unfortunately, in the darkness and swift currents of the St. Lawrence, several of the British ships ran aground on the Îsle-aux-Oeufs and the expedition was abandoned.

Although the memory of their visit was to be documented well into the 19th century, the Kings’ trip to London had little significance in the broader scope of American history. French power persisted in Canada until the fall of Montreal in 1760. And with the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes region were opened to English settlement.

Ironically, the westward movement of colonists towards Iroquois lands led to the eventual collapse of the Five Nations. And after 1763, a series of military, political, and economic disasters compounded these and other problems.

Sources:

Bond, Richmond P. (1952).Queen Anne’s American Kings Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Thwaites, Reuben G. (ed.). (1896-1901). The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, Vol. 30: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791; The Original French, … and Notes; Hurons, Lower Canada, 1646-1647 73 vols. Cleveland: Burrows Brothers.