Plains Tribes

The Great Plains is the huge area in the central portion of the North American continent which stretches from the Canadian provinces in the north, almost to the Gulf of Mexico in the south, from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Mississippi River in the east. This is an area which contains many different kinds of habitat: flatland, dunes, hills, tablelands, stream valleys, and mountains. It is a dry region and lacks trees except along rivers and streams. Plains Indians are those which are most often stereotyped by movies and other media as representing all Indians. The buffalo, the horse, and the tipi are all important items in Plains cultures.

Lower Plains:

Arkansas | Louisiana | Oklahoma | Texas

Upper Plains: Iowa | Kansas | Minnesota | Missouri | Nebraska | North Dakota | South DakotaUpper Mid-West: Illinois | Michigan | Ohio | Wisconsin

The Plains Indians are the indigenous peoples who live on the plains and rolling hills of the Great Plains of North America. Their equestrian culture and resistance to domination by Canada and the United States have made the Plains Indians an archetype in literature and art for American Indians everywhere. Plains Indians are usually divided into two broad classifications which overlap to some degree. The first group became fully nomadic and dependent upon the horse during the 18th and 19th centuries, following the vast herds of buffalo, although some tribes occasionally engaged in agriculture; growing tobacco and corn primarily. These include the Blackfoot, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Gros Ventre, Kiowa, Lakota, Lipan, Plains Apache (or Kiowa Apache), Plains Cree, Plains Ojibwe, Sarsi, Nakoda (Stoney), and Tonkawa.

The second group of Plains Indians includes the aboriginal peoples of the Great Plains, as well as the Prairie Indians who come from as far east as the Mississippi River. These tribes are known as the Lower Plains Tribes or Southern Plains tribes. They were semi-sedentary, and, in addition to hunting buffalo, they lived in villages, raised crops, and actively traded with other tribes. These include the Arikara, Hidatsa, Iowa, Kaw (or Kansa), Kitsai, Mandan, Missouria, Omaha, Osage, Otoe, Pawnee, Ponca, Quapaw, Wichita, and the Santee Dakota, Yanktonai and Yankton Dakota.

Southern Plains

Southern Plains Villagers occupied the Southern Plains from 800 CE to 1500 CE. These Indian people had an agricultural economy which they supplemented by hunting and gathering wild plants. With regard to hunting, the bison was an important animal and was also important in the religious life of the people. Overall, the Southern Plains Villagers had a rich and varied subsistence base.

The Southern Plains Village sites were relatively small, ranging from a half an acre to as large as four acres. They were usually located on major streams or tributaries. These were sites where the fertile sand-loam soils were well-suited to their corn-based agriculture.

Several small communities would often be clustered fairly close together which suggests a rural community composed of several family groups. In some instances, a larger site would serve as the central community for a number of smaller sites which would be located up and down the river valley.

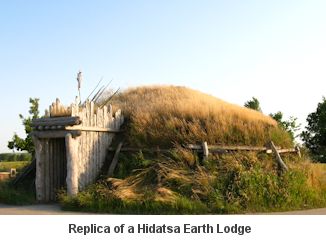

Southern Plains houses tended to be square or rectangular, and made with central support posts. Upright logs placed in postholes were used to form the walls. The walls of the houses were plastered. The houses were roofed with grass thatch. Houses averaged 23 feet long by 14 feet wide.

The Southern Plains Villagers made flaked stone tools from both locally available materials and from materials which had been traded through some distance. They used arrowheads which archaeologists classify as Fresno, Washita, Ellis, and Edgewood types.

The Plains villagers used a variety of ground stone tools, including grinding stones. They also used different types of abrading stones. The sandstone abraders which they used were similar to graded sandpaper. They would be used in making bone tools. Coarse abraders would be used for the initial or rough out work. Then the toolmaker would switch to the medium abraders for intermediate steps. Finally they would use the fine grade for finishing work or re-sharpening.

Using stone tools for grinding corn and plant seeds meant that there was a large amount of grit in the food. This resulted in tooth wear.

The Southern Plains Village people also made pottery. Some of the pottery was made using a limestone temper while some was made using a shell temper. In general, the pots were made for everyday use and tend to have little or no decoration. In addition to pots and bowls, they also made pipes and figurines from clay. The clay figurines were used in fertility ceremonies and the clay pipes were used in tobacco smoking ceremonies.

The Plains Village people used cache pits for storage. These were dug into the ground to a depth of about 4 feet and they were slightly more than 3 feet in diameter.

During the Turkey Creek Phase (1250 to 1450) in Oklahoma, there were trading networks which connected the Southern Plains Villages to the Pueblo villages in the west and the Caddoan groups to the east and northeast.

About 1500 CE, the Southern Villagers appear to have abandoned their heartland and become more dispersed. In some areas of the Southern Plains, the number of sites decreased and there is a substantial increase in the size of the remaining villages. It is possible that climatic conditions forced the people to move eastward where water supplies were more reliable. Some of the Southern Villagers were the ancestors of the historic Wichita. Intrusive groups, such as the Kiowa, began to appear at this time.

Northern Plains

After the Indian Nations on the Northern Plains acquired the horse in the eighteenth century, warfare became more common. Northern Plains warfare, however, was very different from the warfare waged by European countries and later by the United States: it was not usually waged by one tribe against another. War was not waged to conquer other nations. While there were battles in which people were killed, the purpose of war was not to kill people.

Warfare was carried out by small, independent raiding parties rather than by large, organized armies. The motivation for war was personal gain, not tribal nationalism. Through participation in war an individual gained prestige, honor, and even wealth. Since wealth among the Indian nations of the Northern Plains was measured in horses, warriors could increase their wealth by capturing horses from other tribes.

Honor and Prestige:

For Plains Indian warriors, warfare centered around counting coup. “Coup” is a French word indicating “blow,” but for the Indian warrior coup was a war honor. A warrior did not count coup by killing the enemy or collecting scalps or capturing sexual slaves. While it was not uncommon for warriors to kill their enemies in battle, this was not in itself considered to be a particularly noteworthy act of valor.

The actual act of counting coup varied somewhat from tribe to tribe. Among the Cheyenne, for example, the act of counting coup involved touching an enemy with a stick (known as a coup stick), bow, whip, or the open palm of the hand.

Among the Blackfoot, the highest war honors were given to capturing an enemy’s gun. Also ranked high was the capture of a bow, shield, war shirt, war bonnet, or ceremonial pipe. The taking of a scalp ranked below these things.

During the nineteenth and much of the twentieth century many of the written and popular media accounts of Indian warfare stressed the practice of scalping. Yet among the Plains tribes, a scalp was not highly valued: it was simply an emblem of victory. Taking a scalp was not the goal of combat.

Warfare, according to Sioux writer Dr. Charles Eastman was about personal courage and honor:

“It was held to develop the quality of manliness and its motive was chivalric or patriotic, but never the desire for territorial aggrandizement or the overthrow of a brother nation.”

Wealth:

In addition to the acquisition of honor and prestige, war was about gaining personal wealth. An individual who had many horses could gain a great deal of prestige, particularly if he also gave away many horses. Wealth was something that was shared, it was not hoarded nor was it passed down to family members. Wealth had to be earned as it could not be inherited.

Since the objective of many war parties was to capture horses, it was common for the party to leave their camp on foot. If they were going to capture horses, there was no use in taking horses with them.

Religion:

Plains Indian warfare was closely intertwined with religion, but not in the manner of the Europeans. Warfare was never waged because of religious differences. First of all, Plains Indian religions were generally based on animism rather than theism. In animistic religions, spiritual entities communicate with the people through dreams. Thus, a war party might form because a warrior would announce: “I had a dream…..” and those who felt that the dream was strong would join the war party. These dreams of war would usually describe where horses might be captured.

Success in war was generally attributed to the warrior’s individual spiritual power, not to the superiority of a religion, religious belief, or god. Religion, like warfare, was a highly personal thing. War medicine was often acquired through dreams and fasting. War medicine often involved a war song, face paint, and a sacred object to be worn during raids.

Military Strategy:

The military strategy for Plains Indian warfare involved the avoidance of unnecessary risks. From the viewpoint of Indian warriors, craft and cunning were superior to courage. To raid an enemy camp and to capture horses without being detected was a primary goal. Thus the American Corps of Discovery lead by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark lost half of their horses to a raid by Crow warriors and yet they never saw the warriors.

While war parties had nominal leaders, each warrior really fought alone. The goal was personal glory, not tribal victory. If a warrior saw a sign that indicated failure, the warrior might turn around and go home. This was a personal spiritual experience and no-one, including the war party leader, could insist that the warrior continue with the party.

Since surprise was a key element in Indian war strategy, war parties often travelled at night, attempting to avoid detection. The war party would travel in single file with the war leader taking the lead and young men on their first raid traveling in the rear. During the day they would try to stay hidden.

Warfare and the United States:

When the United States military first encountered the Indian nations of the Northern Plains in battle, the army did not understand either Indian military strategies or Indian motivations for fighting. The Indian warriors were not following the rules of war as understood by the Americans. The idea of warriors as individuals who did not follow orders and who could leave the field of battle whenever they wanted created in the minds of the military a stereotype of Indian warriors as cowards.

On the other hand, when Indian warriors first encountered the U.S. Army, they were baffled because the U.S. did not follow the well-established rules of war. The Army fought in the winter; it required soldiers to follow orders even when following them meant sure death; it sought to kill people rather than acquire honor; and it sought to obtain land and religious conversion.

Hasinai

Hidatsa, North Dakota

Iowa (Ioway), Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma

Kaw (Kansa, Kanza), Oklahoma

Kiowa, Oklahoma

Kitsai (Kichai), Oklahoma

Mandan, North Dakota

Missouri (Missouria), Oklahoma

Omaha, Nebraska

Osage, Oklahoma

Otoe (Oto), Oklahoma

Pawnee (dialects: South Band, Skiri), Oklahoma

Ponca, Nebraska, Oklahoma

Quapaw, Oklahoma

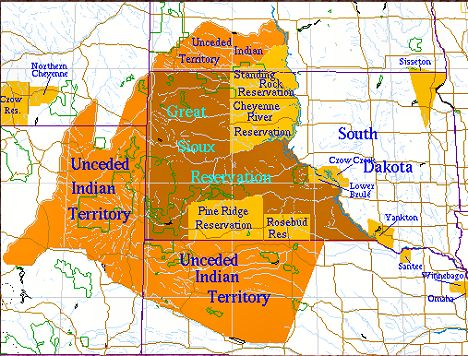

Sioux (Also see Sioux Tribes Overview)

Dakota, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan

Lakota (Teton), Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Saskatchewan

Stoney, Alberta

Assiniboine (Assiniboin), Montana, Saskatchewan (Fort Peck Indian Reservation is home to Assiniboine and Sioux)

Tonkawa, Oklahoma

Tsuu T’ina (Sarcee, Sarsi, Tsuut’ina) ,Alberta

Turtle Mountain Chippewa Indians of North Dakota

Wichita (Affiliated Tribes − Wichita, Waco, Tawakoni, Keechi), Oklahoma

Plains Tribes

Anishinaabe (Anishinape, Anicinape, Neshnabé, Nishnaabe) (see also Subarctic, Northeast Woodlands. Wabanaki Confederacy)

Ojibwa (Chippewa, Ojibwe), Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Saskatchewan, Manitoba

Saulteaux (Plains Ojibwe, Nakawē), British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba

Chippewa Cree, Montana

Ottawa (Odawa), Oklahoma

Potawatomi, Kansas, Oklahoma

Apache

Jicarilla Apache, New Mexico

Lipan Apache, New Mexico, Texas

Mescalero Apache, New Mexico

Plains Apache (Kiowa-Apache), Oklahoma

Aranama

Arapaho (Arapahoe, Arrapahoe), Oklahoma, Wyoming

Besawunena

Nawathinehena

Atsina (Gros Ventre), Montana

Besawunena

Blackfoot and Blackfeet

Kainah (Blood, Blackfoot), Alberta

Northern Peigan (Blackfoot), Alberta

Southern Piegan (Blackfeet), Montana

Siksika (Blackfoot) Alberta

Caddo

Cheyenne Montana, Oklahoma

Chickasaw Oklahoma

Comanche, Oklahoma

Plains Cree,(Chippewa-Cree), Montana

Crow, (Absaroka, Apsáalooke) Montana

Hasinai

Iowa (Ioway) Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma

Karankawa Texas

Kaw (Kansa) Oklahoma

Kiowa Oklahoma

Kitsai

Missouri tribe (Missouria) Missouri

Nawathinehena

Omaha Nebraska

Mississaugas

Osage Nation Oklahoma

Otoe ( also spelled Oto) Oklahoma

Ottawa Michigan; Oklahoma

Pawnee (Dialects: South Band, Skiri) Oklahoma

Ponca Nebraska, Oklahoma

Quapaw (Arkansas) Arkansas, Oklahoma

Sauk (originally Great Lakes now Kansas, Oklahoma, Iowa)

Seneca

Sioux (Lakota, Dakota, Nakota) Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota

Lakota (Sioux) (a.k.a. Lakȟóta, Teton Sioux or Titonwan)South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska

Northern Lakota (Húŋkpapȟa, Sihásapa)

Central Lakota (Mnikȟówožu, Itázipčho, Oóhenuŋpa)

Southern Lakota (Oglála, Sičháŋǧu)

Brule Sioux

Oglala Sioux

Eastern Dakota (Sisseton or Dakhóta), North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa

Santee (Isáŋyathi: Bdewákhathuŋwaŋ, Waȟpékhute)

Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ)

Western Dakota (a.k.a. Yankton-Yanktonai or Dakȟóta or Middle Sioux)

Yankton (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ)

Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna) (a.k.a. Nakoda or Nakota)

Assiniboine (singular:Assiniboin)

Santee Sioux

Stoney

Tamique

Three Affiliated Tribes

Arikara (aka Arikaree or Ree), North Dakota

Hidatsa, North Dakota

Mandan, North Dakota

Tonkawa Oklahoma

Tsuu T’ina (Sarcee, Sarsi, Tsuut’ina)

Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians of North Dakota

Wichita Oklahoma [Affiliated Tribes – Wichita, Waco, Tawakoni, Keechi]

Wyandot Ontario, Michigan

Plains

Aranama

Arapaho Wyoming, Oklahoma

Arikara (aka Arikaree or Ree) North Dakota

Assiniboine Montana Fort Peck Indian Reservation is home to Assiniboine and Lakota (Sioux)

Atsina

Besawunena

Blackfoot Montana/Alberta (bands: Kainah or Blood, Siksiki, Northern Peigan, Piegan or Blackfeet)

Brule

Caddo

Cheyenne Montana, South Dakota; Oklahoma

Chickasaw Oklahoma

Comanche Oklahoma

Crow (Absaroka or Apsáalooke) Montana, South Dakota

Chippewa Cree, Montana

Plains Cree Montana

Dakota

Gros Ventre

Hasinai

Hidatsa North Dakota

Iowa (Ioway) Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma

Karankawa Texas

Kaw (Kansa) Oklahoma

Kiowa Oklahoma

Kitsai

Lakota (Sioux) South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska

Lipan Apache

Mandan North Dakota

Missouri tribe (Missouria) Missouri

Nawathinehena

Oglala Sioux

Plains Ojibwe

Omaha Nebraska

Mississaugas

Osage Nation Oklahoma

Otoe ( also spelled Oto) Oklahoma

Ottawa Michigan; Oklahoma

Pawnee (Dialects: South Band, Skiri) Oklahoma

Piegan

Plains Apache (Kiowa-Apache)Oklahoma

Ponca Nebraska, Oklahoma

Quapaw (Arkansas) Arkansas, Oklahoma

Santee Sioux

Sauk (originally Great Lakes now Kansas, Oklahoma, Iowa)

Siksika

Sioux (Lakota, Dakota, Nakota) Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota)

Stoney

Tamique

Teton Sioux

Tonkawa Oklahoma

Tsuu T’ina (Sarcee, Sarsi, Tsuut’ina)

Wichita Oklahoma [Affiliated Tribes – Wichita, Waco, Tawakoni, Keechi]

Wyandot Ontario, Michigan

Yankton Sioux

Yanktonai Sioux

Arctic

California

Northeast

Great Basin

Great Plains

NW Coast

Plateau

Southeast

Southwest

Sub Arctic