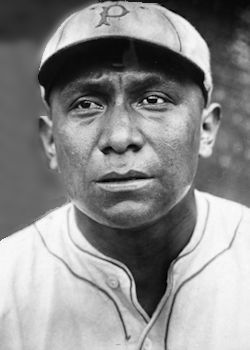

Mose J. Yellowhorse from the Pawnee tribe is considered to be the first full-blooded American Indian to play in baseball’s big leagues.

Alternate Name: Moses YellowHorse

Alternate Name: Moses YellowHorse

Tribe: Pawnee Birth: January 28, 1898, Pawnee, Pawnee County, Oklahoma

Death: April 10, 1964, Pawnee, Pawnee County, Oklahoma

Burial: North Indian Cemetery, Pawnee, Pawnee County, Oklahoma

Mose J. Yellowhorse was the son of Clara and Thomas Yellow Horse, both of whom had walked to Oklahoma during the relocation of the Pawnee from Nebraska to Oklahoma in 1875.

Though not as long a journey as other Trail of Tears tribes endured, it was just as arduous, with many dying of disease and starvation. In 1879 the population of the Pawnees was reported at 1,440, which was a drop of fifty percent in 15 years.

Thomas and Clara met in Oklahoma Territory, married, and settled down on a 160 acre farm.

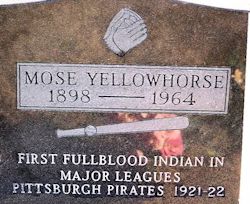

It was there in Oklahoma Territory, that Mose J. YellowHorse was born on January 28, 1898. Todd Fuller shows that the unusual spelling of his first name is correct in 60 Feet Six Inches and Other Distances from Home: The (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse. Although he was known as Moses in later years, and signed his name that way during his baseball career, his name was probably first misspelled when he attended the Chilocco Indian School. Further proof that his name was actually Mose and not Moses, is that Mose is the spelling engraved on his gravestone.

The Pawnees appeared to have been assimilated more easily into the mainstream of Euro-American life than did other tribes. Yellow-Horse and his parents wore white men’s clothes and lived in a permanent structure on their own farm. He attended school as ordered by the Indian Agency, an order intended to acculturate him into American society. With this background he fit more easily into the broader white society.

Despite this acculturation, Moses YellowHorse retained some of his tribe’s ancient customs and language. For a millenium the Pawnees had a rich history, and they did not give it up easily. Yellow Horse was quite knowledgeable about his tribe’s culture and augmented his knowledge of it all of his life.

The Pawnees, rich in religion and mysticism and whose history went back many centuries, were herded into camps in the Oklahoma Territory. The tribe was divided into four bands: Skidi (Wolf Band), Kilkihaki (Little Earth Lodge Band), Tsawi (Asking for Meat Band), and Petahauirata (Man Going Downstream Band). The Yellowhorse family belonged to the Skidi or Wolf Band of Pawnees.

Yellow-Horse performed as a child in the Pawnee Bill Wild West Show and, according to the story of his relative, Albin LeadingFox, learned how to throw a baseball by hunting rabbits and birds with rocks to help feed his family.

Moses attended the Federal Indian School at Chilocco, Oklahoma, where, in addition to his studies, he honed his baseball skills and love of the game. In 1917, at the age of 19, Moses was playing both varsity ball and semi-pro ball.

Moses attended the Federal Indian School at Chilocco, Oklahoma, where, in addition to his studies, he honed his baseball skills and love of the game. In 1917, at the age of 19, Moses was playing both varsity ball and semi-pro ball.

By 1920, he helped pitch the Travelers of Little Rock to the Southern Association Championship, sporting a record of 21 wins and 7 losses.

At the end of that winning season, Barney Dreyfuss, owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, purchased YellowHorse’s contract from the Travelers. Dreyfuss brought the 22-year-old pitcher to Pittsburgh, quickly propelling him into the history books.

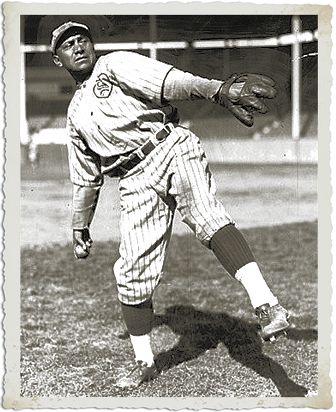

The 5-foot-10, 180-pound right-hander pitched for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1921 and 1922 after compiling a 21-7 record with Little Rock in the Southern Association in 1920. He was 5-3 with a 2.98 earned run average during his first season.

Baseball was prospering after surviving the “Black-Sox” gambling scandal of 1919, but the “national pastime” had other practices, notably concerning race, that today would be considered scandalous.

Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis did nothing to eliminate the league’s policy of barring non-whites. Landis, according to one account, “was arbitrary, anti-minority, anti-immigrant, anti-woman, anti-nonwhite and anti what he called ‘sissies,’ meaning all those who were interested in things of a cultural nature.”

An unrelenting foe of integration, Landis made little effort to disguise his racial prejudice as commissioner from 1920 to 1945.

Despite the existence of many talented black players, Landis sabotaged efforts to integrate them into the majors. Club owners also would not budge from the league’s “white only” policy,insisting that white players would not play alongside blacks, that white fans would not attend games in which blacks played, and that hotels would not house black players on road trips.

As a result, blacks established their own baseball teams and leagues.

In 1919, Andrew “Rube” Foster, considered the “father of black baseball” and one of the most influential figures in the sport’s history, proposed to Landis that one black team join the National League and another join the American League.

Landis turned the proposition down, and in 1920 Foster held a meeting with other black owners that ultimately resulted in formation of the Negro National League. Pittsburgh boasted two of the league’s finest teams, the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords.

Although Native-Americans were not formally banned from baseball, Barney Dreyfuss’ signing of Moses Yellow-Horse flew in the face of tradition. YellowHorse was a full-blooded Pawnee, the likes of which had never worn a Major League uniform.

From time to time, a few “mixed-blood” Native-Americans —notably Jim Thorpe, “Chief” Bender, and “Chief” Meyers —had made it to the majors. Jim Thorpe, unquestionably America’s most outstanding Indian athlete, was of French and Irish descent as well as a member of the Sac and Fox tribes. Thorpe played outfield for the New York Giants from 1913 to 1917 and was part of the 1917 Giants World Series team. He later was selected by the Associated Press as America’s best all-around male athlete of the first half of the twentieth century. His picture appeared on Wheaties cereal boxes after children from the Pawnee Reservation started a letter writing campaign to the cereal company.

Charles A.”Chief” Bender, a star pitcher for the Philadelphia Athletics from 1903 to 1914, was part German as well as part Chippewa. Bender appeared in five World Series and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1953.

John T. “Chief” Meyers was a mixed-blood member of the Cahuilla tribe of California and a graduate of Dartmouth College. Myers, a catcher with the New York Giants from 1908 to 1915 and with the Brooklyn Dodgers in1916, played with the Giants in three World Series games and appeared with the Dodgers in their 1916 World Series debut.

Of the many Native Americans who played in the majors, Mose was neither the first (Louis Sockalexis, Penobscot, starred in the 1890s with the Cleveland Spiders—later called Indians, an absurdly ironic tribute when one considers the grotesquely racist nature of the team’s “Chief Wahoo” caricature) nor the best (Charles “Chief” Bender, Ojibwa, pitched his way to Cooperstown; Allie “Superchief” Reynolds, Muscogee, tossed two no-hitters for the Yankees in 1951; Rudy York, Cherokee, was one of the American League’s premiere sluggers in the years just prior to World War II) and a half-dozen others had longer, more productive careers. But he was the first full-blood Indian to play Major League Baseball.

Of the many Native Americans who played in the majors, Mose was neither the first (Louis Sockalexis, Penobscot, starred in the 1890s with the Cleveland Spiders—later called Indians, an absurdly ironic tribute when one considers the grotesquely racist nature of the team’s “Chief Wahoo” caricature) nor the best (Charles “Chief” Bender, Ojibwa, pitched his way to Cooperstown; Allie “Superchief” Reynolds, Muscogee, tossed two no-hitters for the Yankees in 1951; Rudy York, Cherokee, was one of the American League’s premiere sluggers in the years just prior to World War II) and a half-dozen others had longer, more productive careers. But he was the first full-blood Indian to play Major League Baseball.

The color line had not been invoked in the cases of Thorpe, Meyers, Bender, and others, possibly because of their mixed ancestry. But how did a “full-blooded” Indian like YellowHorse gain entry into the league?

For one thing, Pirate owner Dreyfuss was a powerful force, and Commissioner Landis, although quite prejudiced against blacks, was intrigued by YellowHorse’s Indian heritage.

Landis’ fascination with YellowHorse was so great that in the spring of Yellowhorse’s first season with the Pirates, Landis summoned manager Gibson and YellowHorse to his chambers. After their meeting, highlighted by a question and answer session, Landis was impressed with the Pirates’ latest addition.

Once back in Pittsburgh for the home opener, YellowHorse became the first Pirate pitcher to win a home opener in his rookie season. Touted by many as the best rookie find of the year, newspaper men bestowed upon Yellowhorse the moniker “Chief,” although he held no such status among his people.

Yellowhorse made his debut with the Pirates on April 15 in relief of Earl Hamilton in a 3-1 win over Eppa Rixey and the Cincinnati Reds. He made a few starts but was used mainly as a relief pitcher.

The fans in Pittsburgh accepted YellowHorse. Indeed, they were swept up in frenzied support of their “favorite Indian.” In a short time, YellowHorse acquired quite a vocal following. During home games, the chant “Put in YellowHorse” would build slowly but steadily into a crescendo until the whole of Forbes Field reverberated.

Periodically the chant was accompanied by beating drums, unintelligible war whoops and foot stomping. This adulation never adversely affected YellowHorse, who typically strode towards the pitchers mound, threw a few warm-ups, and proceeded with the business at hand. YellowHorse threw only one pitch —a “smokin’ fastball”— which some said was clocked at 97 mph.

In just four months, he became a favorite among fans in Pittsburgh and throughout the league. The possibility of YellowHorse appearing in a game almost assured the respective team owners of a record number of customers.

YellowHorse’s acceptance by baseball fans throughout the league was remarkable. He roomed with the team and was not segregated on the road, as was Jackie Robinson after the latter’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1940s. Moses was accepted as a full member of the Pittsburgh Pirate franchise. In fact, on one outing to play the New York Giants, the team, including YellowHorse, stayed at the posh Ansonia Hotel on New York’s Upper West Side.

YellowHorse’s presence did provok resentment among a few fans and white players, who felt he had no business on the playing field.

On September 26, 1922, for example, YellowHorse was facing Ty Cobb in an exhibition game. Cobb as usual was crowding the plate and according to witnesses was hurling racist remarks at YellowHorse, who shook off four pitches and then sent a fastball that hit Cobb right between the eyes. The Tiger bench rushed the mound, but YellowHorses’s teammates ran out to protect him.

In the early part of the twentieth century, most Native Americans were subject to numerous racist laws and practices. Some states had laws against intermarriage between Native Americans and whites, and did not permit Native Americans to attend school with white children.

Indians living on reservations were not recognized as citizens of the United States until 1924. Prior to that, they had been deprived of property rights, not permitted to vote, and were not afforded equal protection of the law.

In some Western states, Native Americans, especially those of darker skin color, were prohibited from staying in white motels or eating in white restaurants, and were relegated to menial jobs or worked as migrant workers.

Native Americans suffered discrimination because some in society fostered a stereotype that considered them lazy and untrustworthy, malingerers and drunkards. Unfortunately, the few native americans who had made it to the major leagues did little to change the widely held stereotype, which is still believed by some people even today.

Most fell victim to alcohol, a malady instrumental to many ballplayers’ demise, not just specifically native american players. YellowHorse was no exception.

On one occasion, “while intoxicated and carousing in the area adjacent to Forbes Field,” he was found to be belligerent and creating a disturbance. A police officer arrived to find YellowHorse in need of a bottlecap remover and bleeding from using his teeth to open beer bottles. The officer and an unnamed Pirate subdued him and got him home. This was not the last time YellowHorse would succumb to the destructive influences of liquor.

YellowHorse’s promising rookie season was cut short when he sustained a groin injury requiring surgery. In 10 games, YellowHorse’s 5-3 record had helped the Pirates finish the 1921 season in second place behind New York. A healthy YellowHorse might not have significantly altered their finish,but he was sorely missed by the team and fans.

In 1922, YellowHorse was fully recovered from his groin injury and eagerly awaited the start of a new season. According to a local newspaper, YellowHorse was in the best shape and condition of all the Pittsburgh players. He believed he had much to prove. However, that was not to be the case.

In a game against the Cardinals on July 5, 1921, YellowHorse suffered a rupture in his arm that required surgery. This put him on the injured list for two months. Hurting his arm again in 1922 (possibly from a drunken fall) began his tailspin.

By June of that season, manager Gibson was replaced by hometown favorite Bill McKechnie amid charges of heavy drinking by unnamed ballplayers and a general lack of discipline onthe team.

Fingers pointed at Moses YellowHorse and his roomate, Pirate shortstop and future Hall of Famer Walter “Rabbit” Maranville, but nothing was ever proven.

Unfortunately, Moses J. YellowHorse for much of his life contributed to the stereotype of the drunken Native American. Some stories say Rabbit Maranville introduced him to alcohol. Other stories say Pirates manager Bill McKechnie decided to room him with shortstop Rabbit Maranville because they were both problem hellraisers, and McKechnie also roomed with the two to try to keep them in line.

One night while the skipper went to a movie, the roommates decided to do their drinking at the hotel. They also began catching pigeons from their 16th-story hotel window and stuffing them in McKechnie’s closet.

When he got back to the hotel, the manager was surprised to see the pair asleep, but he got an even bigger surprise when he opened his closet.

Dissatisfaction with YellowHorse began to surface among Pirate fans. An October newspaper account predicted that “as a pitcher and player his days are few.” Ironically, this was the same newspaper that in 1921 had touted him the “best all-round player,” and in 1922 had considered him “the best player (physically) to come out of Spring training.” Nor was YellowHorse meeting the expectations of the owners.

His drinking and disruptive behavior did little to dispel well-engrained stereotypes of Indians. One may surmise that many in baseball considered YellowHorse a threat to the status quo.

As the 1922 season wore on, YellowHorse’s effectiveness waned, both as pitcher and as a crowd pleaser. The alcohol had a deleterious effect on his performance; Dreyfuss and McKechnie were disheartened. In August, YellowHorse contracted severe tonsillitis and was again hospitalized.

His second year came to an abrupt end, after appearing in 28 games, compiling a 3-1 record and 4.52 an earned run average, and batting a respectable .316.

His big-league career was over.

He pitched briefly for a time in the minor leagues, but with his history of alcoholism and hell raising preceding him, no big-league team was willing to take a chance.

In December of 1922, YellowHorse was traded to the Sacramento Senators of the Pacific Coast League.

Between 1923 and 1924, YellowHorse played sporadically in the minor leagues. Perhaps his finest season was 1923 with the Sacramento Senators. As the ace of the pitching staff, he helped pitch the Senators to a second-place finish,ending the season with a 22-13 record and an E.R.A. of 3.68.

By the middle of the 1924 season, YellowHorse was finished, even with the minors. He injured his arm again midway through the season, and at age 28, returned home to Pawnee, Oklahoma.

There, he sunk even further into his alcoholism and worked a string of low paying jobs until 1945. At that time, he finally stopped drinking and began to turn his life around. He retrieved his dignity, and found steady work with the Oklahoma Highway Department.”

Once he regained his sobriety, YellowHorse tirelessly donated time and energies to tribal concerns, especially to the younger members, and was eventually considered an Elder of the tribe. He helped establish youth baseball, often serving as coach, occasionally umpiring semi-pro games, and pitching when the need arose.

From 1945 until his death, YellowHorse lived a clean and respectable life. He became a groundskeeper for the Ponca City Ballclub in 1947 and coached an all-Indian baseball team of youngsters who were all full-blooded. He hunted and fished and made decisions as an elder of the tribe.

He also spent many hours schooling the youth in Pawnee traditions, ceremonies and language, which were disappearing. Though schooled in the white man’s ways, YellowHorse never abandoned his Pawnee heritage.

By the early 1960s, YellowHorse’s place in Pawnee society was solidified, and he was held in high esteem. His positive influence on Pawnee youth was evident. The tribe honored YellowHorse on his 66th birthday. A feast and ceremonial war dance were given in recognition of his accomplishments past and present. However, the specter of death stepped forward and three months later, on April 10, 1964, Moses YellowHorse died of an apparent heart attack.

The residents of Pawnee saw to it that he had a proper burial and headstone. He was buried with the traditional Pawnee ceremonies and interred in the North Indian Cemetery in Pawnee, Oklahoma. His headstone curiously shows only the years of his birth and death but no dates. His gravesite is tucked away in a far corner of the Indian part of the cemetery separated from the white section by a long row of cedar trees.

The residents of Pawnee saw to it that he had a proper burial and headstone. He was buried with the traditional Pawnee ceremonies and interred in the North Indian Cemetery in Pawnee, Oklahoma. His headstone curiously shows only the years of his birth and death but no dates. His gravesite is tucked away in a far corner of the Indian part of the cemetery separated from the white section by a long row of cedar trees.

YellowHorse never married and had no children.

In his honor, an annual softball tournament was initiated, and by the late 1960s a housing project was erected bearing his name.

YellowHorse’s death in1964 was reported in local papers but received no mention in any Pittsburgh newspapers. But in 1970, his name resurfaced in Pittsburgh, showing he had not been entirely forgotten by Pirate fans.

As the city and the Pirates readied a new stadium, a debate swirled over what to call it.The Pittsburgh Press, in an article entitled “Stadium Name Game Took Some Funny Hops Along the Way,” listed various names, legitimate and sarcastic. Some suggested that it be named Pie Traynor Field in honor of one of the most revered Pirates of all time, or Flying Dutchman Field to honor Honus Wagner. Others with an eye for colorful titles leaned toward Chief YellowHorse Stadium. In the end, the park was christened simply “Three Rivers Stadium.”